Gerrit Smith

- Anti-Slavery Activity

Throughout his activist career, Gerrit Smith regarded himself an

Abolitionist. Originally a supporter of the American Colonization Society,

which was involved in exporting black missionaries to Liberia, Smith was

gradually (and apparently grudgingly) moved closer to the camp of William LLoyd

Garrison by the deliberate efforts of his associates as well as unplanned

circumstances. Through their attacks on the Colonization Society, the

Garrisonian's flushed out that Society's opposition to the abolition of

slavery. Faced with the open expression of this posture on the part of the

Society, Smith felt himself obliged to withdraw. In so doing he paid up in

advance the support he had previously pledged to the Society.

Smith differed with Garrison on both principle and tactics. While Garrison

held the US Constitution to be a pro-slavery document, Smith relied on the

interpretation of Lysander Spooner that it was in fact a pro-liberty document.

He frequently cited the argument that the framers rejected a bed to have the

word "slavery" introduced into the Constitution, accepting its

original fugitive slave provisions only when the term "fugitive from

service" was substituted. While Garrison held that political action was to

be avoided, Smith helped to found the Liberty Party, and helped to convert

Frederick Douglass to his views.

A strong influence upon Smith's decision to leave the Colonization Society

was his associate the

Rev. Beriah Green. Green was the President of the

Oneida Institute, an interracial college at Whitesboro, near Utica, that was a

center of Abolitionist activity. Green (after whom Smith named his only son to

reach adulthood) actively encouraged Smith to abandon the Colonization Society,

and to join with Garrison's American Anti-Slavery Society. Smith had been

reluctant to do so, and had published a statement of his differences with the

Garrisonian's. When a convention was held at Utica for the purpose of

organizing a New York Anti-Slavery Society, Smith accepted Green's invitation

to attend.

The convention was held on October 21, 1835, a day that appears to have been

fateful in the history of the anti-slavery cause. Smith and his wife attended

the Utica convention while on the way to visit Smith's father in Schenectady.

When the convention was broken up by a local mob, Smith invited the group to

reconvene the next day at Peterboro, where he assured they would be welcome to

continue their activities. He and his wife immediately set out for home, and at

3:00 AM he reportedly began writing his Crime of the Abolitionists

speech, to be delivered the next day. He also wrote that on his arrival at

Peterboro, he and others armed themselves in defense against any pursuers from

Utica. None came.

On the same day, Abolitionist gatherings were also broken up in New England.

Garrison was led through Boston streets by a rope, before being rescued by

police. It was the sight of the victimized Garrison that reportedly stirred

Wendell Phillips to join Garrison, providing the movement one of its most

forceful speakers.

When the New York Anti-Slavery Society convened in the

Presbyterian Church in Peterboro, resolutions were

passed to seat Smith and the other Peterboro abolitionists. Smith rose to offer

his resolution supporting the free speech rights of the Abolitionists, and

condemning those who would limit them. He also said:

It is not to be disguised, that a war has broken out between the North and

the South. - Political and commercial men are industriously striving to restore

peace : but the peace, which they would effect, is superficial, false, and

temporary. True, permanent peace can never be restored, until slavery, the

occasion of the war, has ceased. The sword, which is now drawn, will never be

returned to its scabbard, until victory, entire, decisive victory, is our or

theirs ; not, until that broad and deep and damning stain on our country's

escutcheon is clean washed out - that plague spot on our country's honor gone

forever ;- or, until slavery has riveted anew her present chains, and brought

our heads also to bow beneath her withering power. It is idle - it is criminal,

to hope for the restoration of the peace, on any other condition.

Smith went on to say the Abolitionists would not seek their aims with "carnal

weapons" but "Truth and love are inscribed on our banner, and 'By

these we conquer.'"

For some time Smith remained committed to the peaceful, and generally

political/legal opposition to slavery. A year after announcing to the newly

formed New York Anti Slavery Society that he was not yet ready to join, he was

elected its President. In the years to come, Smith supported the Abolitionist

cause with speeches, money, and his own direct support to those fleeing to

Canada. His home was a major way station on the Underground Railroad, where

others were provided the opportunity to hear first hand the stories of persons

escaping from slavery. The story of Harriet Powell is one such, notable for the

local intrigue as well as for the impression that meeting Powell had on Smith's

young cousin, Elizabeth Cady (Stanton).

Smith subscribed to and supported

several Abolitionist newspapers, including the Liberty Press, edited for a time

by James Caleb Jackson, whom he brought to Peterboro. When Congress was

considering the passage of a Fugitive Slave Law, Smith organized a

convention at Cazenovia that made news throughout the

country. When efforts were made to enforce Secretary of State Daniel Webster's

May 1851 promise to execute the law "in Syracuse, during the next

anti-slavery convention" the stage was set for Smith's involvement in the

dramatic rescue by force of a fugitive from the custody of federal marshals. Smith subscribed to and supported

several Abolitionist newspapers, including the Liberty Press, edited for a time

by James Caleb Jackson, whom he brought to Peterboro. When Congress was

considering the passage of a Fugitive Slave Law, Smith organized a

convention at Cazenovia that made news throughout the

country. When efforts were made to enforce Secretary of State Daniel Webster's

May 1851 promise to execute the law "in Syracuse, during the next

anti-slavery convention" the stage was set for Smith's involvement in the

dramatic rescue by force of a fugitive from the custody of federal marshals.

For the next seven years, Smith gave the address at annual commemorations of

the Jerry Rescue. The 1858 program also included

speeches by Frederick Douglass and Thomas W. Higgison. A year later all three

would be implicated in the preparations for John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry,

an event most readers believe to be expressly foretold in his

letter declining to participate in the Jerry Rescue

celebration of October 1859.

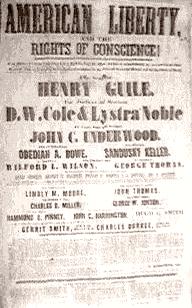

In the 1850's Smith remained active in the attempt to fight slavery through

legal means. The campaign poster shown here details plans for the fateful

October 1851 convention of the NYS Liberty Party at Syracuse (the next

anti-slavery convention following Webster's speech), as well as the events

that led to the dissolution of the Party in 1848. Smith is named (lower left)

as the Party's candidate for President. In fact, Smith was elected to Congress

in 1852, serving one frustrating term trying to advance an agenda that had

several "peculiarities" listed in his thank you letter

to the voters of the counties of Oswego and Madison.

During Smith's tenure in Washington, his daughter Elizabeth

displayed the fashionable version of the so-called Bloomer costume credited to

her innovation.

As dissolution of the Union crept ever closer, Smith became increasingly

frustrated, and increasingly accepting of the use of violence as an instrument.

He joined a group of Massachusetts Abolitionists in lending support to the

anti-slavery struggle in Kansas, and ultimately in support of John Brown's plan

to set up a permanent base of operations in the mountains of Virginia. In the

period leading up to the raid on Harper's Ferry, Brown made frequent visits to

Smith and his associates, and discussed the outline of his plan not only with

Smith and his New England supporters (the secret six), but also with Jermain

Loguen, Harriet Tubman, and Frederick Douglass. The ill-fated

Harper's Ferry raid and its aftermath devastated

Smith, and provoked a psychotic episode that followed an extended period of what

appears to be manic activity on Smith's part.

When war finally broke out between North and South, Smith became a strong

and vocal supporter of the Union cause. After Emancipation, he joined Douglass

in advocating the priority of black suffrage, a position that further distanced

him from the position of his cousin and the other feminists who had united with

others in the cause of Equal Rights for all. He remained throughout his life an

advocate for African Americans, in his final printed circular blaming the

Republican Party for its failure to assure legislation to protect their civil

rights.

Throughout his career Smith presented a striking model of the committed

abolitionist who truly believed in, and advocated for, the equality of all

persons. Nowhere in his public or private papers is there any sign of the

latent or overt racism displayed by many of his contemporaries. He was also, in

this regard, distinguished from many of his colleagues in the reform movements.

|